This is the story behind the story

Katie Langloh Parker was a white woman who notated the Aboriginal language Euahlayi [i] and collected the Legends from the Noongahburrahs (ii) in the later decades of the 19th century. But her publication of the Noongahburrah Legends is controversial and there have been both critical and supportive critiques of her work, yet little on the woman herself who accomplished something extraordinary as a 19th century squatter's wife in the outback.

My intent was to find out more about Katie not to delve into the Legends themselves. That needs to be done by those with the cultural permissions and knowledges to do so. I do not have these permissions and knowledges. That work will be for others, who do.

My Quest

I wanted to learn about the current response to the woman and her work, particularly and importantly, by the Aboriginal descendants of Bangate Station which is on Euahlayi country in north west New South Wales where Katie and her husband, Langloh Parker lived for 20 years.

My quest started like this. I had been chatting to an old friend, the historian Bob Reece, who was mad about Daisy Bates. I remarked to him I had a lot of books about my house by a Katie Langloh Parker – Aboriginal Legendary Tales (Legends) and some more. I remembered some of the stories were read to me as a child. They terrified me. But like so many of my generation that was about all I ever heard or read about indigenous Australia and indigenous Australians. I knew she seemed to have been some sort of relative of mine, as the name Langloh had been in the family for generations.

‘You must, you must’ said Bob, ‘do something on her: a PhD…she’s worth a book’, And indeed she is but this is just a beginning.

Bangate Station homestead in the 19th century*

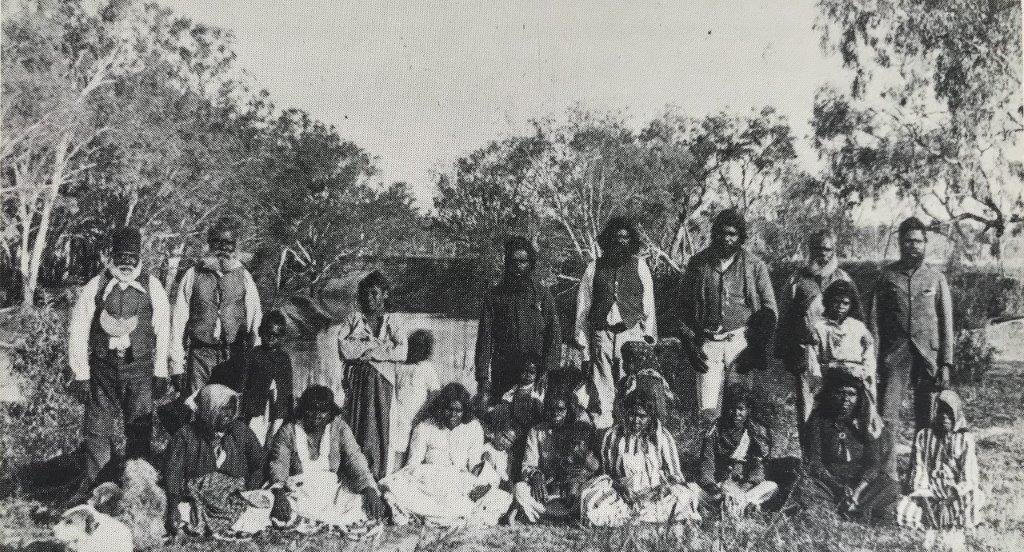

Bangate Station workers. Peter Hippi “King” of the Noongahburrahs is likely the man standing far left**

The more I looked the more extraordinary it seemed that in her early twenties in the 1870s she embarked, not on the life of a traditional squatter’s wife on Bangate Station, but on a serious ethnographic and linguistic journey, and that so very little had been written about her. Was she just another exploitative Victorian colonial or a genuine and useful amateur ethnographer who wrote before any formally trained ethnographers or linguists had been out to the north west of New South Wales to actually see what they were opining about.

As a journalist who has worked in print, radio and television journalism for much of my life, I puzzled over why so much of the writing about her work, its relevance and biases, did not demonstrate any consultation with the Aboriginal descendants of Bangate. They know of her work, use it and can be both grateful and critical. By the way, Katie turned out to be my great, great aunt by marriage. Her husband, Langloh Parker was my great, great uncle.

I applied for a Fellowship at the Mitchell Library and was successful. Thank you Mitchell Library for giving me the privilege.

The journey

I drove the 1400 or so kilometres up to Bangate and back, several times. I went to Walgett, Lightning Ridge and Goodooga to meet the indigenous descendants of the Euahlayi tribe who lived there long, long before the settlers came, but stayed and worked for the Parkers, living on Bangate until they were forced off their land by the Government; and I met as well the whites who knew of them. To libraries and galleries in Melbourne, Canberra and Adelaide.

This is a story of a remarkable woman and how some of the descendants of those who lived on and around Bangate and others with Euahlayi heritage, think of Katie and her work. With interest, with distress or as useful? It covers much of what has been written about her and her publications and importantly, whether the Legends should have been published at all, as their publication may have broken sacred or esoteric law with catastrophic effect. It also looks at her apparent ambivalence, for example her description of Aborigines as my 'darkie friends', (patronising possibly even then) versus her understanding that she had settled on 'their land.'

As Yuwaalaraay (Euahlayi) woman, historian and film maker, Frances Peters Little says:

‘It's nearly forty years since there was a book on Parker and what she achieved, whether that be judged for the better or that her publication of the Noongahburrah/Yuwaalaraay legends broke sacred law. It's time for a new look and time today's descendants had their say.’

So this is my attempt which I call 'not a book - not a PhD' and I hope it serves to remind us of her work, its importance so many years after her first publication in 1896 and adds a little to our knowledge of an extraordinary woman and her extraordinary achievement.

Katie Langloh Parker*

[i] Euahlayi has a number of English spellings, Euahlayi is the spelling used by Katie Langloh Parker and the spelling used in What Katie Did other than in direct quotes or publications but Yuwaalaraay and Yuwalaraay are now used commonly.

[ii] Few Noongahburrah people are believed to survive and indigenous descendants of Bangate now, are essentially Euahlayi people.

* Images from the National Library of Australia.

** These images are archival photographs which have appeared widely over many years but may not be considered appropriate today. They are included as an important part of Katie Langloh Parker’s work and the history of the Noongahburrah and Euahlayi people.

*** Image from the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.